African American Artists at Paulson Bott Press: An Interview with Pam Paulson and Rhea Fontaine

In its 20-year history, Paulson Bott Press has worked with an unusually high number of African American artists, including Edgar Arceneaux, Radcliffe Bailey, McArthur Binion, Thornton Dial, the Gee’s Bend quilters, Lonnie Holley, David Huffman, Kerry James Marshall, Martin Puryear, Lava Thomas, and Gary Simmons. Kenneth Caldwell sat down with Pam Paulson and Rhea Fontaine to talk about their experiences with some of these artists.

A number of the artists you’ve invited to make prints with you have been African American. Was there an intentional strategy?

Pam Paulson: We saw that there was a real vacuum to be filled. There was no one really representing artists of color in a big way.

Rhea Fontaine: And not just in fine art print publishing, but in the larger art world.

PP: Prints are democratic. They make an artist’s work affordable, giving more people the opportunity to get into the art market. We’ve always wanted to have wide-ranging conversations with a broad audience. At the same time, whenever we invite artists to work with us, it’s because we respond to their art.

RF: There is a real moment right now for artists of the African Diaspora in institutions because audiences want to see these voices better represented. I was at the Whitney Museum’s inaugural exhibition, America Is Hard to See, and it was so good to see paintings by Al Loving, Alma Thomas, Noah Purifoy, and many others who, at points, were overlooked by history.

Talk about how you ended up working with the Gee’s Bend quilters.

PP: I went to New York at the end of 2002 and took my family to the Whitney Museum when the Gee’s Bend quilt show was there. We saw the beauty in the patterns and the improvisational genius. Their work was the visual equivalent of jazz.

Then my dad, who was in his mid-80s at the time, was at my house one night, and I was showing him the catalog for the show. I told him, “I was so blown away by this, Dad. You would have loved it.” And he said, “Why don’t you make prints for them?”

But we needed a way in. We couldn’t just walk into Gee’s Bend and ask these ladies to come make prints. We hit a lot of dead ends. Finally I called up Radcliffe Bailey, who had told me he had been to Gee’s Bend. I asked him, “Would you drive down there with me? I want to see if I can get some of the quilters to make prints with me.” The next night, he was at a dinner in Atlanta with a group of art people, and Matt Arnett was there—and Matt’s family represents the Gee’s Bend quilters. Radcliffe knew Matt because they grew up in the same town. He sat next to Matt and said, “My friend Pam, who I make prints with, wants to make prints with the Gee’s Bend quilters.”

Matt called me the next day. Then we were on the phone for the better part of a week. He really wanted to make sure that we were sincere and in no way going to take advantage of the quilters. He was also really interested in taking their work out of the purview of craft and putting it under the purview of art. The show at the Whitney had started to do that, of course, but working in another media besides quilting was going to take it one step further.

At one point, I said to Matt, “If they come and we don’t get anything, I don’t care. I’m just in it for the experience of trying.” And he was satisfied with that, so the quilters came to our studio.

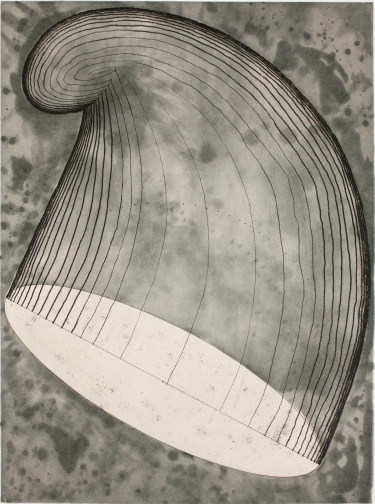

RF: It was our first time working with textile-based artists. Pam and Renee devised this idea of working with soft ground. We had no idea that the translation would even meet our expectations, but it far exceeded them. I came in the day after our printers started working with the quilters, and there were already so many works on the walls. It’s like we dove into a whole new world.

PP: It was so rewarding. It was like being at church. There was a lot of song and praise and gratitude going on while they worked. It was one of the most fun projects we’ve ever done.

Then after we did the prints, we took them to the print fair in New York the next year, and Jo Carole Lauder from the Foundation for Art and Preservation in Embassies saw them. She asked us to do prints with the quilters for their program. So four of the quilters did an edition of 50, and they are placed in US embassies worldwide.

After Gee’s Bend, David Huffman and Lonnie Holley came, didn’t they?

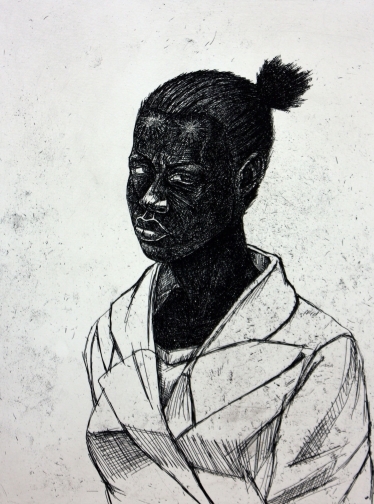

RF: Yes. David is a good friend and someone whose work I have admired for many years. He is the first artist we published who was working with the stereotypical iconography of race in America. One of his early characters, named Trauma Eve, made a major impact on me. His fearless exploration of themes related to the legacy of slavery, postindustrialism, Afrofuturism, and the counterculture continue to fascinate.

How did Lonnie Holley come to work with you?

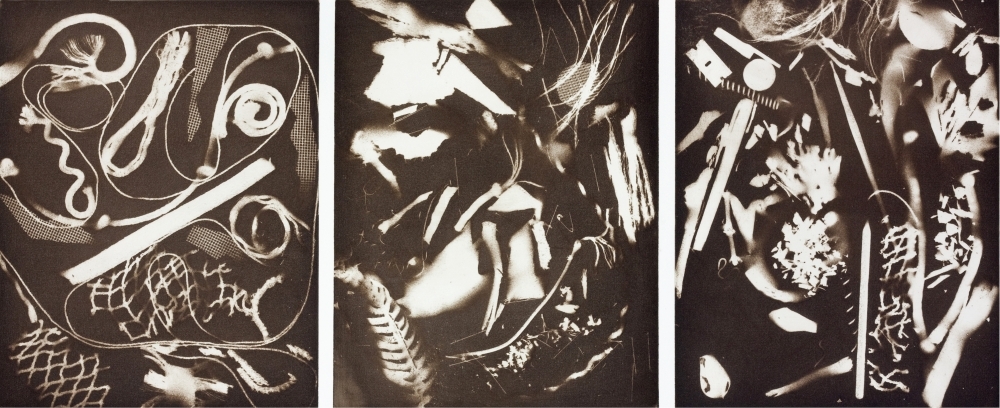

PP: The Arnetts have a large collection of artworks by self-taught artists from the South. After the Gee’s Bend experience, we went down the Arnetts’ Atlanta warehouse, which is gigantic, and talked about all the different artists they collected. Lonnie Holley was in their collection—his sculptures using found objects were beautiful. Lonnie also introduced the Arnetts to Thornton Dial, a groundbreaking African-American artist known for his large-scale assemblages using found objects.

RF: People like the Arnetts, who support the Gee’s Bend quilters, and Lowery Stokes Sims, whose pioneering work at the Metropolitan Museum and the Studio Museum in Harlem introduced so many minority artists to larger audiences—these are the people who are taking risks that others aren’t willing to take, saying things that other people aren’t willing to say, seeing things that other people are not seeing. We’ve always wanted to connect ourselves with that type of visionary. Because of them, a number of extremely talented artists have become known to us and the world at large.