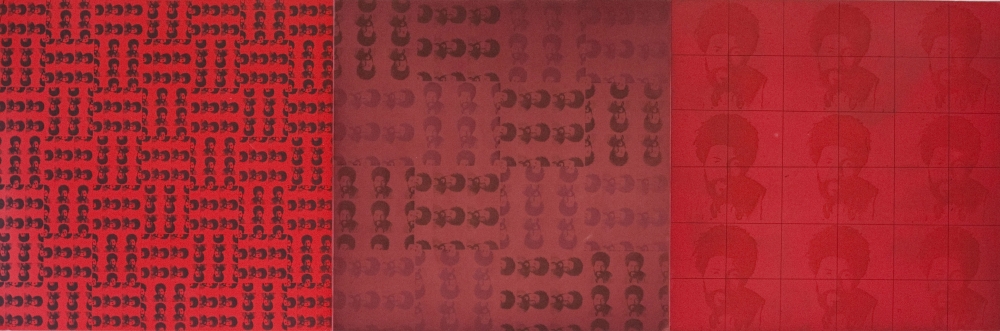

Category: Alicia McCarthy

MINE: New Etchings by McArthur Binion and Alicia McCarthy

The exhibition Mine brings together new works by McArthur Binion and Alicia McCarthy. Re:Mine is the title of a print by Binion as well as the title of the first monograph of his work. Both Binion and McCarthy bring their very personal and emotional content to the minimalist grid.

Binion often makes his marks with a monotonous, task-based approach that speaks to his personal history of manual labor in the cotton fields of the South. He also explores this history by using personal ephemera, images of his birth certificate, a handwritten phonebook, and photos on which he paints. Over the past 50 years, he has developed a unique visual language through the fusion of minimalism and narrative: Binion calls this his “handmade geometry.”

Although visually abstract, Alicia McCarthy’s works are intensely intimate and often include an indication of physical presence. The art critic Roberta Smith writes that McCarthy’s woven paintings “combine handmade quirkiness and a personal, slightly visionary geometry with an echoing perceptual subtlety.” Her graffiti sensibilities—her need to tag or mark a space as her own—appear in her work in the form of a ring left by a coffee cup, a shoe print, or a note written by the artist. In her project at Paulson Fontaine Press, McCarthy used old ink mixes from past projects, bringing a specificity of time and place into her etchings. McCarthy’s print Z.P.R.R.A.Y uses the first initials of the entire staff at Paulson Fontaine Press and becomes another memento of a shared experience.

The Mission School at Paulson Bott Press

In a 2002 article for the San Francisco Bay Guardian, critic Glen Helfand coined the term “Mission School” to describe the work of Barry McGee, Margaret Kilgallen, Chris Johanson, and other young artists who were based in the Mission District at the time and drawing influences from graffiti, comic books, social activism, and the grit of urban living. Paulson Bott Press has had the opportunity to collaborate with a number of these artists, and as part of the press’s 20th anniversary, Pam Paulson and Rhea Fontaine sat down to talk about their experiences with the Mission School.

How did you first become involved with the Mission School artists?

Pam Paulson: In 1998, the Headlands Center for the Arts contacted us. They wanted us to collaborate with an artist to make a gift print. Margaret Kilgallen was one of the artists on their list. We knew about her work and liked it, so we chose her. Afterward, Margaret recommended that we work with Chris Johanson some day. When Chris came to us a few years later, he recommended Shaun O’Dell. All the Mission School artists were very connected to each other and supportive of each other.

Today these artists are celebrated, but what was your experience with them early on?

PP: The first time we went to Chris Johanson’s studio, I remember thinking it looked like a bombed-out building. His studio had holes in the floor, and there was just debris everywhere. This is where he made his art.

Rhea Fontaine: They were young artists with no interest in money, and they had an openness to neighborhoods that were considered more fringe.

Margaret and Tauba Auerbach—their early work seemed to share something.

RF: They were both influenced by sign painting, typography and book arts early on. When Margaret was getting her MFA at Stanford, Tauba was an undergrad there. And like so many other fans, Tauba was influenced by Margaret’s work. Tauba’s first job out of college—and I think I remember her saying it was much to her parents’ dismay—was sign painting at the New Bohemia Signs shop in San Francisco. She loved it, and it influenced some of her early text-based and calligraphic paintings. When we were working with her on our second collaboration, she announced that she had quit the sign shop and was going to pursue painting full time. It was a very big moment for her.

How did the Mission School come to such prominence?

RF: There were some key players who were nurturing that talent and promoting it here and also outside the Bay Area. Jack Hanley Gallery was a big part of that, as well as the Luggage Store Gallery and Adobe Books—Chris Johanson met his future wife and fellow artist, Johanna Jackson, at Adobe Books, by the way. But the attention that Margaret Kilgallen and Barry McGee received for their really innovative styles was key. They began a movement without even knowing it. Of course, all of these other artists that we’re talking about now were working in the Mission at the same time, like Alicia McCarthy, (who we’re so excited to have worked with finally).

They all came from very different backgrounds, didn’t they?

RF: Tauba Auerbach had creative parents, so she was raised around art and went to Stanford. Chris Johanson was more self-taught. He was part of an earlier punk/skate/zine scene that influenced younger artists like Tauba Auerbach, among so many others. So they’re coming from completely different worlds, and I think they’re both true to the worlds they’ve come from.

PP: Alicia McCarthy was born and raised in Oakland, and she’s also a musician, and part of a multi-genre community that many of these artists worked in. She has a really mischievous soul. Her dad works on cars, like Tauba’s dad. I think she grew up around people putting things together and taking them apart, and just saw everything as a component to something else. So when she worked on found objects, I think she had just a real eye for that material. That unites her with Johanson and the rest of the artists. When she was working with us, for instance, she saw the scratched back of an old plate, and that’s what she wanted to use in one of her prints.

How did Clare Rojas become involved with the Mission School artists?

PP: She was a fan of Barry and Margaret’s and met them back east. She had a passion for their work, and she was a musician too.

RF: She sent them some of her recordings, and they fell in love with her music.

PP: Margaret died in 2001 from breast cancer, a few weeks after giving birth—she was only 33. Some time after that, Clare moved to San Francisco. She saw a real need to help Barry with his daughter Asha—and then things fell into place.

RF: They got married.

Talk about Jack Hanley. He seems like a central character in all this.

PP: He had a gallery in the Mission at the time. He’s a musician too. As long as I’ve been in the art world, he’s had a gallery.

RF: Jack likes taking risks on people who most galleries would never have paid attention to. He has a real eye for talent. I can remember Jack supporting artists in legal battles over graffiti charges. A lot of these artists were really living a hand-to-mouth existence back then.

But then Jack moved to New York in 2008?

RF: Yes, now he has a gallery in the East Village. It was a big loss for the Bay Area when he moved. He showed a lot of New York artists here. He’s always been very avant-garde. He was one of the people who suggested we work with Keegan McHargue.

PP: Now the Mission School artists have spread out, and they’re refining their work and growing up.

It’s an interesting time for art that’s rooted in resistance.

RF: As an artist matures and wants to continue being a working artist—there is this dance that needs to happen between their work and the institutions that support them. That’s an interesting thing to navigate for artists who’ve built legacies out of shunning the system. The show by Barry McGee at the Berkeley Art Museum a few years ago was really interesting. Just looking at his installation, you could feel him grappling with being in a museum space. There’s an ongoing and constant tension in the work of all of these artists, a conflict that you can’t help but feel.