October 25, 2014 through January 10, 2015

The idea for this show emerged from an ongoing interest in the idea of spectacle—specifically, Andy Warhol’s engagement with the subject. His Death and Disaster series embraced the horrific image to construct a commentary of historical trauma. Roger Kamholz wrote, “Warhol took the senseless tragedies of his time, ones that expressed the fractures and failures of the American dream, and presented them as history painting, in the tradition of grand, wrenching statements like Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819) and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937).”

Thinking more about this show and spectacle, I realized that in Aristotle’s outline of tragedy, spectacle is just one part of his thinking. “Horror Story” is really a show about the tragedy of violence.

Christopher Brown’s prints Continental and Flag are depictions of stills from the Zapruder film. Edgar Arceneaux’s etching 1968 depicts the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Brown uses cheesecloth on softground plate to create the look of a TV screen, and Arceneaux depicts the Starship Enterprise in the far distance of his image, making both interpretations feel a bit detached from the actual events. Arceneaux’s Beyond the Great Eclipse series depicts ephemera from the Watts riots of 1965. All of these tragedies continue to haunt our perceptions of the 1960s.

Examining the horrors of the slave trade, David Huffman’s print Remuneration, 2007, along with Radcliffe Bailey’s Passage Gorée, 2011, are chilling portraits of the architecture built in order to traffic human beings.

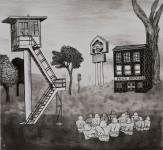

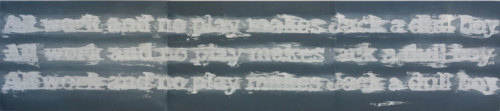

Perhaps it is the horror film genre that can best engage traumatic history and confront viewers with it. Gary Simmons’ All Work and No Play references Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining. Simmons often uses metaphor and American popular culture to create works that address personal and collective experiences of race and class. In Kubrick’s film, there are several shots of Native American architecture, and the hotel is filled with Native American décor. The hotel, built on a sacred Indian burial ground, was haunted due to this desecration. Many theorize that the film is exploring the early American settlers’ exploitation and killing of the Native Americans.

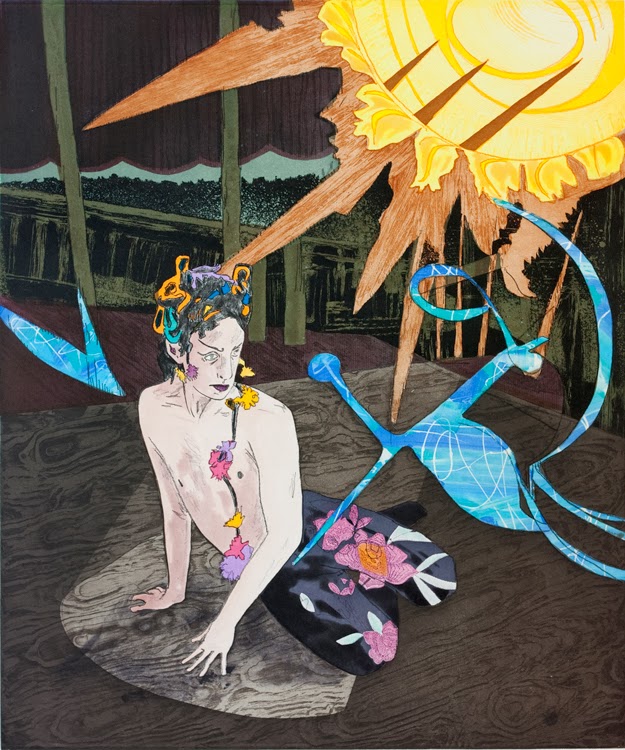

Again referencing film, Hernan Bas’ prints The Tenant and The Previous Tenant are images of the protagonist in Roman Polanski’s Film, Le Locataire, or The Tenant. The film explores the violence of the loss of privacy and the theme of victimization. Kota Ezawa’s prints Man and Woman and Stairs depict the scenes on the Odessa steps from the classic film Battleship Potemkin. The film terrifies the viewer with images of the brutal massacre of dozens of defenseless men, women, and children.

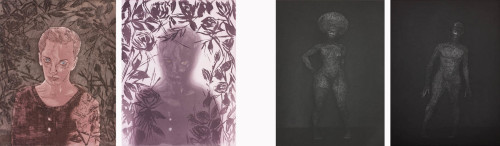

Lastly, Kerry James Marshall’s Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein address Mary Shelley’s classic novel and its racial resonances in the United States. Elizabeth Young, author of Black Frankenstein, states that “these Black Frankenstein stories effect four kinds of racial critique: they humanize the slave; they explain, if not justify, black violence; they condemn the slave owner; and they expose the instability of white power.” Again, Kerry James Marshall uses metaphor to explore the violence of slavery.

-Rhea Fontaine