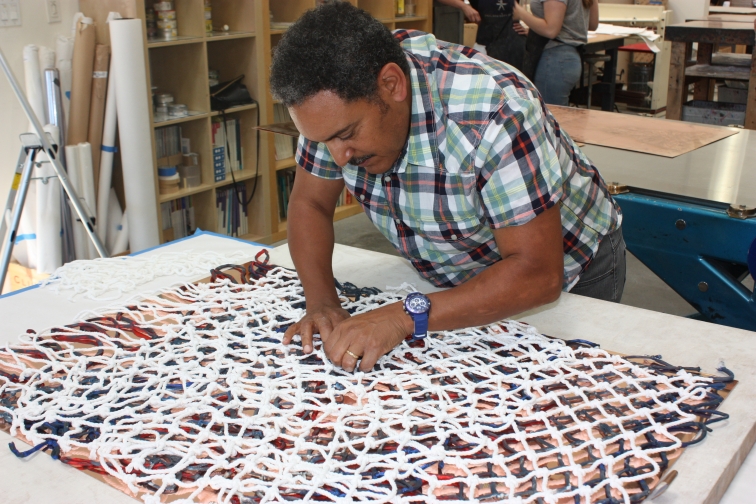

A glimpse inside the printmaking studio at Paulson Fontaine Press with Oakland-based artist David Huffman.

Category: David Huffman

Interview with David Huffman

David Huffman grew up in Berkeley, California in an activist household during the 1960s civil rights movement. In 2007, David’s first prints with the press worked with stereotypical American racial iconography. He arranged rich compositions that explored identity and socio-political history in a futuristic world of metaphor.

David became known early on for his crew of astronauts he calls “Traumanauts”. On their missions they searched for the inward and outward makings of identity, taken from them by their experience of repression on Earth. His iconic character Trauma Eve, an Aunt Jemima space robot, is unforgettable. Toxic air, poisoned water, and the AIDS virus are no match to her strength. She is a symbol of a particular type of rebelliousness that carries the burden of an embattled past and fights against a history of violence and oppression.

Over the last ten years David has distilled his concerns and issues around identity into basketball abstractions, which he considers social abstractions. Basketball has been an enduring trope in African American art, from the conceptual efforts of David Hammons and Mark Bradford to the charged photos and videos of Paul Pfeiffer.

Can you talk about being raised in Berkeley and how that may have influenced you, your thinking and your work.

David Huffman: When I was a kid growing up Berkeley was definitely in a time of transition. The civil rights movement was percolating and political intrigue was the common topic on the news. The same things that were on the news were happening on the streets, and so protests were a constant performance. Not a performance in the sense that they were fake or pretending, but a performance in the sense that it was something that you actually did. It was like, where were you gonna protest? And who’s gonna make the signs? Everyone would galvanize their families. My Aunt Norma and my mom Dolores were very involved and were friends with Bobby Seale. The first time I carried a protest sign I was about five, so that would have made it 1968. A lot of the picketing we were doing was about fair housing, fair wages and employment. There was this spectrum of social woes that we all felt. At times there was a lot of reluctance on my part because I would rather be watching cartoons on Saturday, but at the same time you couldn’t help absorbing the injustice of things. So I definitely had a default to a kind of fair play because things aren’t fair. And even though I didn’t want to hold a picket sign all the time from age five through eleven, I understood that someone should be doing this, and so why not myself?

Did your mom making visuals for a political movement inform you becoming someone who communicates ideas visually?

DH: My mom was already an artist before she did stuff for the panthers. She did these figures called “Nevers” that were very psychedelic, exotic looking black figures that were mostly women. So she was always making art and I picked up on that. Everybody kind of made a little bit of art. I made some art and my sister made art. Grandmother was an artist for awhile herself. So art was a part of the family growing up. I didn’t think of the protest stuff as art. I just thought oh you have to do this panther thing and you have to silk screen it on stuff and add the text. To me that didn’t look like art at all. Art was always something we kind of did but we didn’t call art, we just drew. We also had a lot of art around the house. We had a lot of original stuff from my mom’s friends and a longtime boyfriend who was a painter. He painted kind of like Van Gogh, so we had these pseudo-Van Gogh paintings framed in gilded frames. It was pretty wild. There were also black light posters. And black power posters, maybe one with a black couple looking perfect with huge Afros laying intertwined, maybe with a panther by them. And we had panther stuff, like a ceramic panther on our table, which was kinda common. We had wicker stuff, the same big wicker chair that Huey had.

That’s become quite a symbol.

DH: Yeah, my aunt gave him one. She thought she gave him the one that they used for the famous photo shoot. But I was talking to Bobby Seale and he remembers when she gave him the chair, and he said the one that they used for the poster was from a house in San Francisco where they did the photo shoot. My aunt always thought it was her chair because she gave it to him around the same time.

Was there something to this wicker chair, or was it just a popular look?

DH: The chair was a part of this connection to Africa that started to gain a lot of attention in African American culture and popular culture in general. It was mostly focused on West African countries and cultures. I remember Swahili was a popular African language that people were trying to learn. So the wicker chair became part of this connection to Africa. The spear and the shield were very popular too. There was kind of a hodgepodge of ethnic accoutrements.

Do you think Berkeley made this exploration easier?

DH: I don’t know because I grew up in Berkeley, so I don’t know how it was in other places, but most people would flock to Berkeley for the energy. We lived right near Telegraph Avenue, right in the heart of the protest area in Berkeley. I remember the really heavy time when Reagan called the national guard out against the protesters. I was maybe five or six years old and it felt like we were under siege. To keep things calm they blocked off streets and barricaded some with barbed wire. To see the national guard come up your street in different vehicles and riot gear, big face visors, shields and clubs was just shocking. It was war. They would run in single and double file and the sound of their boots and the clanging was terrifying. I remember going to a theater right off of Telegraph and seeing the movie “When Worlds Collide,” a very popular science fiction movie at the time, and wanting to get away on a rocket! The premise of the movie was that the moon crashed into the earth and it was going to blow up or disintegrate and they built a rocket for everybody to get on, but it was all white people that got on – haha – and they went to a paradise land. That’s what you wanted to do because it was a very crazy time.

Very stressful.

DH: Yes

Let’s talk about how sci-fi and this idea of escape might influence your work.

DH: In the sixties people were thinking about the space program and the possibilities of looking for another world or finding things outside of planet earth. The space race permeated science fiction narratives and subjects. Take Star Trek for instance, the Enterprise was an advanced ship that could go the speed of light and held a diverse crew. The landscapes of science fiction offered up a new way to deal with issues in life. You felt somewhat free, possibly politically free in these spaces. In sci-fi there is a sense of modern freedom; you can create stuff, imagine things, and lead and steer in your own right. I think that is the element of being a full citizen in any country. During the civil rights movement the fight was to be a citizen and have the same rights, so I think in some ways science fiction offers up the possibilities in that way.

When I started making the Traumanauts they were based on some of the excursions that the Apollo program focused on. I would re-situate the narrative for my own purposes, like the figures would actually be looking at a lynched tree rather than ending up on the moon. I would borrow some of the ways in which they prepared themselves and the ways they interacted with alien spaces. So yeah it became an open space for me to discuss issues about African American culture, history, life and things that I thought were unsaid or perhaps not said enough.

What prompted the shift from narrative and figurative works into abstraction?

DH: I felt like I had said quite bit in those kinds of spaces and I decided to take on paintings as a state of experience. I also began exploring the idea of dark matter. I have always been interested in things that were connected to Nuclear Physics, Astrophysics and Astronomy, and by the 1990s dark matter had become a really compelling subject in science. I was hooked when scientists started discussing dark matter because of all the social and political implications related to the theory. Anything that is unknown gets a dark labeling. So I was curious as to why it was being called dark matter. Was it actually being seen as dark? So I started looking for why it was being called dark matter and it was being discussed as this unrecognizable, unconscious thing that was outside one’s ability to know. And I thought, well these are some of the same qualities of racism too; the way that black people can be abstracted in White American culture. It’s about not knowing, not seeing and labeling in a way that is a whole of not understanding.

I wanted to make work around dark matter and I couldn’t do it narratively. When I first started trying to paint it, I painted this kind of undulating dark space with dark hues and shapes, but it just didn’t solve the content for me in that way. I started looking at how I was using basketballs up until that point narratively and started experimenting by making paintings with basketballs only. The critical mass that started to happen by putting so many basketballs down forced me to think abstractly. It was a different kind of abstraction. An abstraction in a way that black people are abstracted by white american culture, in a way that whites see black people or see through them as invisible. This abstraction has a strong connection to the stereotypical tropes of identity and the icon of the basketball being really loaded as well.

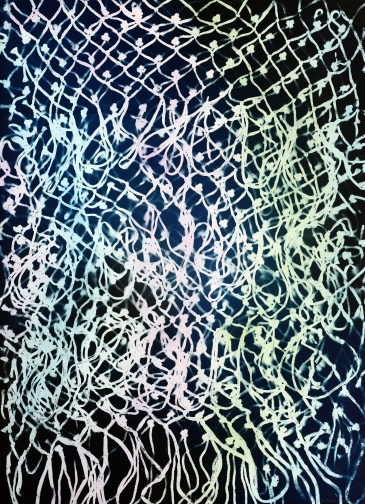

We’re really excited about the new prints that you made with us using basketball nets and chains. How did the process in the studio feel and where is this new work taking you?

DH: Getting the materials and using them in the context of printmaking was really eye opening, because printmaking definitely has its own dynamic. It became a process of just going with what the work was going to do, which doesn’t sound that different than how a lot of artists make work, but for me it was quite different. I have many different strategies that I use when making my work, and I thought I was just going to perform them, but the materials offered up new and surprising choices.

I found it helpful when Pam and the crew came up with suggestions about etching processes. Thinking about “Rainbow” for instance, I was really surprised how that turned out. I was surprised that it was a rainbow, a kind of worn rainbow that perhaps was toward the end, right before it vanished. It captured this elusive nature of rainbows, the feeling of both being sad it was over, but still quite interested that it had occurred at all.

Horror Story: Eight Artists Engage with Mass Culture through Traumatic Imagery

October 25, 2014 through January 10, 2015

The idea for this show emerged from an ongoing interest in the idea of spectacle—specifically, Andy Warhol’s engagement with the subject. His Death and Disaster series embraced the horrific image to construct a commentary of historical trauma. Roger Kamholz wrote, “Warhol took the senseless tragedies of his time, ones that expressed the fractures and failures of the American dream, and presented them as history painting, in the tradition of grand, wrenching statements like Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819) and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937).”

Thinking more about this show and spectacle, I realized that in Aristotle’s outline of tragedy, spectacle is just one part of his thinking. “Horror Story” is really a show about the tragedy of violence.

Christopher Brown’s prints Continental and Flag are depictions of stills from the Zapruder film. Edgar Arceneaux’s etching 1968 depicts the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. Brown uses cheesecloth on softground plate to create the look of a TV screen, and Arceneaux depicts the Starship Enterprise in the far distance of his image, making both interpretations feel a bit detached from the actual events. Arceneaux’s Beyond the Great Eclipse series depicts ephemera from the Watts riots of 1965. All of these tragedies continue to haunt our perceptions of the 1960s.

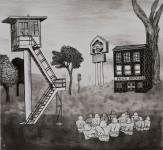

Examining the horrors of the slave trade, David Huffman’s print Remuneration, 2007, along with Radcliffe Bailey’s Passage Gorée, 2011, are chilling portraits of the architecture built in order to traffic human beings.

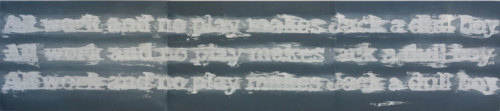

Perhaps it is the horror film genre that can best engage traumatic history and confront viewers with it. Gary Simmons’ All Work and No Play references Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining. Simmons often uses metaphor and American popular culture to create works that address personal and collective experiences of race and class. In Kubrick’s film, there are several shots of Native American architecture, and the hotel is filled with Native American décor. The hotel, built on a sacred Indian burial ground, was haunted due to this desecration. Many theorize that the film is exploring the early American settlers’ exploitation and killing of the Native Americans.

Again referencing film, Hernan Bas’ prints The Tenant and The Previous Tenant are images of the protagonist in Roman Polanski’s Film, Le Locataire, or The Tenant. The film explores the violence of the loss of privacy and the theme of victimization. Kota Ezawa’s prints Man and Woman and Stairs depict the scenes on the Odessa steps from the classic film Battleship Potemkin. The film terrifies the viewer with images of the brutal massacre of dozens of defenseless men, women, and children.

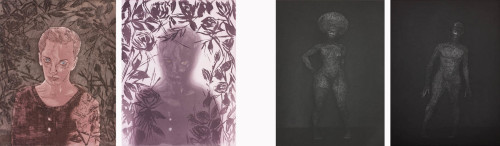

Lastly, Kerry James Marshall’s Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein address Mary Shelley’s classic novel and its racial resonances in the United States. Elizabeth Young, author of Black Frankenstein, states that “these Black Frankenstein stories effect four kinds of racial critique: they humanize the slave; they explain, if not justify, black violence; they condemn the slave owner; and they expose the instability of white power.” Again, Kerry James Marshall uses metaphor to explore the violence of slavery.

-Rhea Fontaine