An Interview with Tauba Auerbach

Interviewer: Tell me what you’re working on here in the studio.

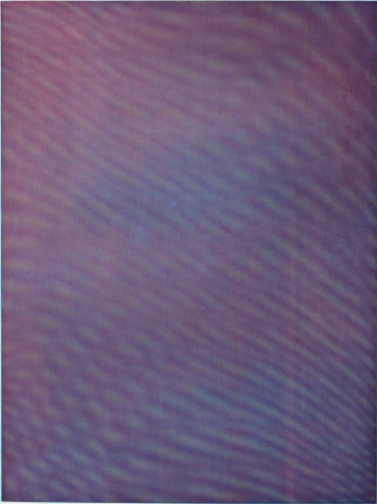

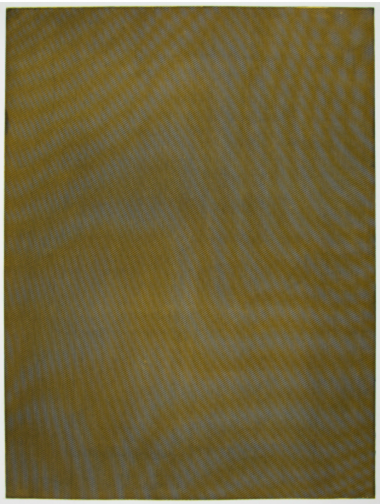

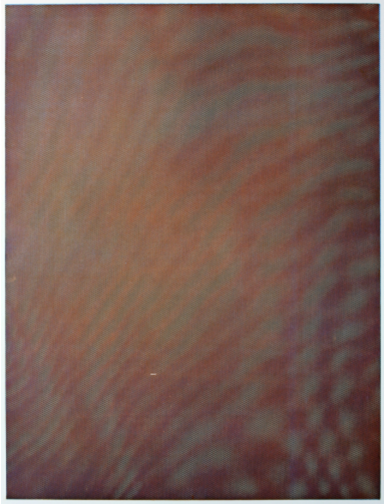

Tauba Auerbach: I’m doing lots of weaving. I’m exploring topological interactions of threads and fibers, using a couple of different techniques. One is this monochromatic system where the contrast in the pieces comes from the difference in the length of the float, which is the term for how long a strip is in the “over” position. In this other type of weaving with two colors, which is something called shadow weaving, it’s a checkerboard weaving pattern. It reverses in some sections, and therefore, the direction of the stripes reverses.

Q: What are you weaving on?

TA: Directly onto the stretcher. First I draw a pattern on the computer using Adobe Illustrator. This pattern isn’t a description of what the piece is going to look like when it’s finished. It’s a description of what position each strip is in. They are like instructions.

Q: Almost like a simple computer program, like we used to do with punch cards?

TA: Yes, but there’s nothing automated about it. I draw every square, but I just benefit from being able to cut and paste on the computer. I make this colored pattern and one person reads the pattern calling out the ‘over’s and ‘under’s, and the other person weaves it.

Q: Do you always stick to the pattern you’ve laid out?

TA: Often, once I get part of the way into weaving, I’ll realize there’s something I don’t like. Then I make an alteration to the pattern.

Q: You go back to the screen?

TA: Yes. This still happens a lot, because I’m still learning how to do this. I’m still making it up. There are some things I can’t predict. For example, I just don’t know how the shadows are going to fall.

Q: The diagram on the computer doesn’t capture light, does it?

TA: I have a flat drawing. And a lot of the visual information you’re getting, especially in the monochromatic pieces, has to do with shadows. Sometimes I make patterns on the computer that look really exciting. And then we weave them, and it looks like nothing. It just looks so flat and boring. There can be other surprises in the good direction, too.

Q: How did this evolve out of what you were doing previously?

TA: I’ve been interested in topology for a long time. That naturally led me to weaving, because when you weave, essentially, you’re working with two complete planes that are changing places over and over again. I also have a fascination with things that I would consider technologies that we don’t talk about as technology anymore, because they’re old, like rope-making and weaving.

Some of the strongest high-tech materials that we use now are woven, like carbon fiber, for example. It’s not just the material properties of the carbon fiber, but also the way it’s arranged that gives it its strength.

As artists, we’re painting on woven material all the time, this sort of invisible support. I thought I’d burrow into the support and into the material and build it back from scratch, in a way.

The third reason is that I was preparing for a show that’s traveling called Tetrachromat. A tetrachromat is a person who has a fourth color receptor on their retinas, whereas the standard human has three. There has been quite a bit of evidence recently that there are human tetrachromats—they’re all women, because this is carried on the X chromosome.

I was trying to imagine what the tetrachromat’s world is like. I developed this monochromatic weaving during that time, because one of the things I learned about likely tetrachromacy is that the mutated, extra receptor would not allow a person to perceive colors outside the normal, standard spectrum visible to humans—like ultraviolet or infrared. The perception would be between the red and the green. There would be a dramatic increase in sensitivity and an ability to distinguish between yellows that look all the same to us, or things around the yellow range. So tetrachromacy is the ability to see variety and maybe depth or light or shadow in things that look the same to most people. Weaving seemed like a natural way to try to investigate that kind of variety within one very simple color or non-color.

Q: Wow. A more mundane question. You cut these strips?

TA: Yes. They come on big spools. There’s a very specific spacing. And at the end, we straighten the whole thing with a big long ruler and push all of the strips into a straight position.

Q: And then you have to unstaple it all and restaple it?

TA: I don’t have to unstaple. We staple all the ones going the horizontal way. When we’re weaving the verticals, we just pin them on the back. Then at the end we pull them really tight and staple.

Q: Tell me more about this technique.

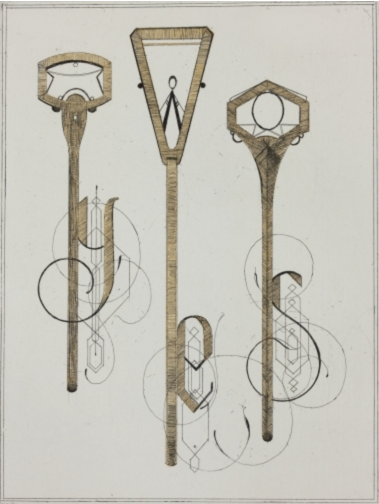

TA: I was doing weaving research, and I came upon this technique called shadow weaving. I think it’s called that because, if you were to isolate this shape, it appears that there’s a shadow on this side and a highlight on that side. By reversing it, you get the stripes running in different directions. And I’ve pretty much only seen it used to create straight shapes. I’m trying to see what can happen with something a little bit more complicated than that. This is only the fifth one that I’ve done using this technique. So I feel like I’m really at the beginning of something with this and not quite sure where it’s going yet.

Q: Do you finish one of these and decide it’s not good enough?

TA: Often.

Q: Then, what happens?

TA: Take it apart.

Q: I remember you commented that with some of the other accidental works that involved broken glass, you threw out an enormous amount of work and started over.

TA: Fortunately, in this case, I can just take them apart and reuse all the materials.

Q: How many don’t work out?

TA: Perhaps two out of every three I take apart or alter in a significant way.

Q: This is after you’ve designed it and woven much of it?

TA: Yeah. Sometimes it’s just taking out a section and reweaving. But I hope to get better at predicting what they’re going to look like.

Q: In one of our conversations a few years ago, you said that there was lot of thought that went into every piece before you made the piece itself. In other words, the work was more in the thinking than the doing. The last time we spoke, you said you were spending less time thinking ahead and more time doing…and then discarding. Now this time it seems like a combination of both approaches.

TA: You’re right. I have to plan it out. But there’s still a lot that depends on accident, a lot that I can’t predict.

Q: You were doing a lot of airbrush before you were using this newer technique. Are you constantly looking for change?

TA: I think change just naturally happens all the time.

This interview with Kenneth Caldwell appeared in the May-July 2013 issues of SFAQ.