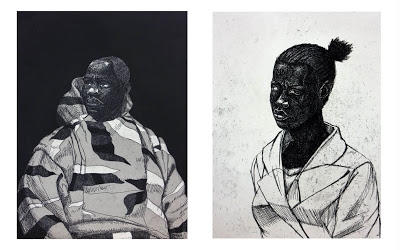

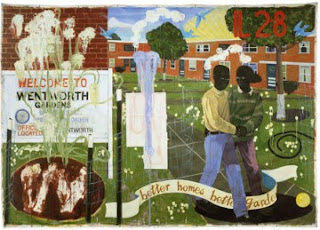

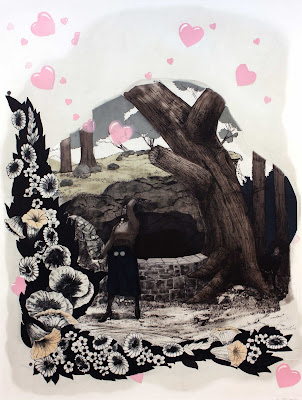

Over the past decade, we have worked with four of the quilters from Gee’s Bend, making numerous prints from quilt tops sewn for this purpose. Two of the quilters, Louisiana Bendolph and Loretta Bennett, along with curator Matt Arnett, joined me in Asheville, North Carolina, last fall to take part in a panel discussion about the translation of quilt to print.

During the panel, Lou and Loretta described their first quilts, made at about age 12. Loretta liked making quilts, and Louisiana did not. Both felt that quilt-making was a practical skill, passed down mother to daughter, whose purpose was to keep the family warm during the winter. Neither saw the practice as art, but as part of the work they had to do alongside farming and cooking.

Warren Wilson College and the Center for Craft, Creativity & Design (CCCD) in Asheville cohosted the exhibition Gee’s Bend: From Quilts to Prints. The show was cocurated by Julie Caro, professor of art history at Warren Wilson, and Marilyn Zapf, assistant director of CCCD. Caro has designed two courses around the quilters of Gee’s Bend: “African American Art: Gee’s

Bend” and “Art History Practicum: Gee’s Bend.” Part of the curriculum included planning the exhibition and teasing out all the layers of transformation; quilts to print, quilter to artist, craft to art, unknown to known.

Warren Wilson began as a school for farm children whose parents could not easily afford a college education. It was designed to allow students to earn their tuition by working: facilities crews, farming crews, and cooking crews took part in the daily labor of running the campus while attending classes. Today, the students get to pay tuition and work; there are landscape crews, plumbing and electrical crews, weaving crews, cattle and pig crews, etc. The idea is to take responsibility and build community by learning the work required in any enterprise.

I joined one of Julie’s classes off-site at the Black Mountain College Museum, which happens to be across the street from the CCCD. We watched a short film from the 1980s about Black Mountain College. It existed from 1933 to 1957 and was a precursor to alternative institutions like Warren Wilson, which is just a short drive over the hill. The film consisted of interviews with a few principle figures from the college explaining its truly democratic ideals. The teachers were the owners and the student had a voice on the decision-making council. John Dewey’s principles of education were the mainstay of the interdisciplinary philosophy. Building community was paramount. Everyone toiled to run the campus, build buildings, and design curriculum. Work equalized the residents.

Josef and Anni Albers fled Nazi Germany directly to Black Mountain College and joined the faculty. The Albers’s Bauhaus ideas helped Black Mountain become an incubator for the American avant garde. Experimental art, music, dance, writing poetry, and science attracted faculty and students. Faculty included Buckminster Fuller, Robert Creeley, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, Ruth Asawa, and Walter Gropius. Students included Robert Arneson, Allan Kaprow, Robert Rauschenberg, Dorothea Rockburne, Elaine de Kooning, and Cy Twombly.

Later that day, Marilyn Zapf took us to see both campuses. Black Mountain is now a boy’s camp, but many buildings remain, modernist structures in sharp contrast to the nearby woodsy cabins.

The discipline of work, the autonomy of enterprise, and the responsibility of completion resonate in all of these places. In the Paulson Bott Press studio, Gee’s Bend, Warren Wilson, and Black Mountain, the practice of work for a common goal becomes a habit that frees us all to push further creatively.

The following day, we were interviewed on NPR by Frank Stasio. You can listen at http://wunc.org/post/artistry-rural-alabama-meets-art-world.