Last September Hung Liu returned to Paulson Bott Press for her fifth project. All of us at the press look forward to her enthusiasm and her wide-ranging humor. The first time I worked with Hung Liu in 2008, I expected her to be stoic and severe, given the heavy content of her work. However, I was surprised and pleased to discover that despite her seriousness, she carries herself with an almost child-like cheerfulness and curiosity. There is a good deal of laughter when Hung is in the studio. She also brings a considerable amount of technical knowledge and confidence to the production of her prints. Intaglio can be a daunting and opaque medium for many artists, but she never seems intimidated by its esoteric challenges and unpredictability. For this project we focused on two large portraits and three small cartoon images based on her Happy & Gay series of paintings.

The Happy & Gay images are based around a series of Chinese Dick and Jane-like cartoons for children. The title comes from a song/school exercise for learning English: “Come boys and girls—let’s sing let’s dance. We are happy and gay. It’s our National Day.” The seemingly benign and bucolic images are both familiar and strange. Like their American counterparts, they’re intended to teach a set of wholesome, normative values such as hard work and pragmatism, with a heavy emphasis on the nuclear family and nationalism. Consequently, the fact that these doppelgangers are in the service of the Maoist Cultural Revolution, the loyal opposition of American exceptionalism, makes them feel, dare I say, queer. Such a contrast brings into focus the puritanical undercurrent in both. Hung goes on to further push these tensions with soft subversions such as the pink clothing, which also evokes the double entendre of the title. Such flamboyance would be contextually deviant even in their American equivalents. The images and phrases of her youth are resurrected, with an irony and an acknowledgement that they no longer embody the meaning they once did.

A former painting teacher of mine once shared a story about a classmate who got in trouble and was ultimately expelled from their academy in the Soviet Union for making an impressionist painting. There was no dissident political content, or satire, just a few fauvist trees, which in an American school would have been at worst derided as quaint or anachronistic. Yet the implied individuality and emphasis on interpretation of feeling were perceived as threatening and subversive to the rigid social order. So in recreating these images in her own hand, and with small expressionistic flares, Hung is slyly breaking the rules that fettered the illustrators and artists forced to work in a state-approved style. In her version, the subjects seem to be tripping the Great Leap Forward.

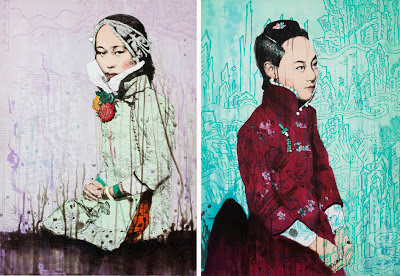

The two portraits are part of an ongoing series of works that are based on early 20th-century photographs of prostitutes. Many of the photographs are small and lack clarity and contrast, yet she is able to enhance the amount of information while imbuing them with a greater sense of life and naturalism. In addition to bringing her large collection of portraits, Hung also brought in an enviable collection of books filled with small reproductions of Chinese woodcuts, which she used to create the backgrounds of Shan-Mountain and Shui-Water. Both prints started with a softground drawing of the figure that was then built up with many layers of aquatint, drypoint, reductive plate work, and, most notably, spitbite, in which nitric acid is painted onto the plate and allowed to drip and run, echoing the turpentine streaks of her paintings. Similar to the way Hung mixes humor and seriousness, these images balance crude or visceral elements with elegance. The softground has a rough, heavy and weathered quality in the way the lines and shapes are broken up by optical chatter, yet the draftsmanship is masterful and sensitive. The spitbite drips can feel both chaotic and ominous, as if the women were melting wax figures yet the drips in and of themselves are lyrical and painted with an unfussy playfulness. These contrasting elements lend a fitting uneasiness to their beauty. While the women are poised and graceful, the images belie the grim and misogynistic reality of their original purpose.

Hung Liu’s work is never what you think it might be at first glance.