Bold Statement

The first time I met Louisiana Bendolph was 10 years ago when she and her mother-in-law Mary Lee Bendolph came to the press in 2005. Both are quilters from the tiny hamlet of Gee’s Bend in Wilcox County, Alabama. The women of Gee’s Bend entered the spot-light in 2003 when their quilts were exhibited at the Whiney Museum of Art. Since that show, their quilts have traveled to numerous national and international venues.

Louisiana stands about 5 foot 4. She is patient and demure and a tiny bit shy, but you can immediately detect strength in her stature.

The stories Louisiana tells of her childhood are vastly different from mine. I am two years her elder, and I remember well the 1970s and my benign day-to-day routine growing up in the suburbs of Boston. Lou’s accounts of those same years reveal a life of hardship that is difficult for me to fathom. She spoke about leaving school to help harvest her family’s cotton crop. They plowed and planted with the help of a donkey. When she talks about her life as a daughter, wife, mother and quilter, her deep connection to her family is evident. Louisiana’s origins give her a straightforward practicality that guides her in times of trouble.

Over the past 10 years, we have done three print projects together. She works in solid colored cotton piecing her work together at the sewing machine. Her compositions are bold and forthright, but her asymmetrical lines are poetic and reveal a complex approach to her art.

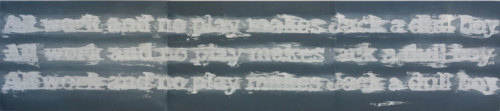

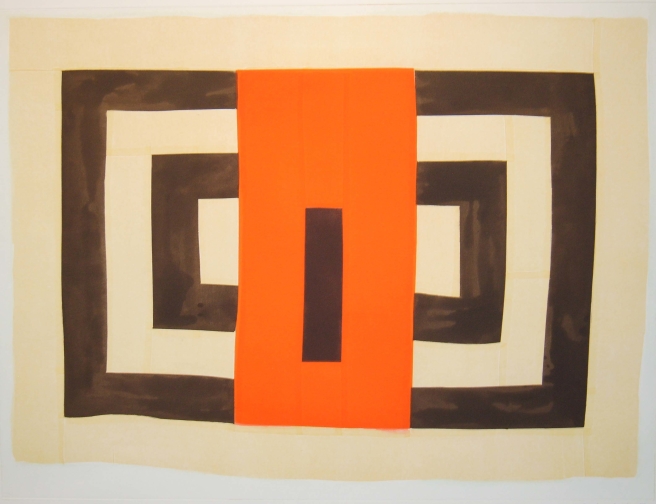

Lou is not afraid to show us her strength. In New Generation, a print she made in 2007, she uses a confident composition of ivory, orange and brown. Alternating colored stripes radiate from a central brown strip. As the title suggests, Lou comes from a new generation of quilters who aim to move beyond the cultural obstacles of their communities’ past.

Her strength includes a willingness to speak frankly about what she believes. In 2007, I watched an unwavering Lou spontaneously take to the podium at a U.S. State Department dinner in Washington D.C. In front of 500 spectators, she thanked her mother and the women in her life, and she thanked the Arnett family for their contributions to her community. Louisiana continually champions the quilters of Gee’s Bend, traveling and speaking to audiences all over the world.

Thinking of Lou’s strength and resolve to usher in a new generation, we are pleased that her print New Generation has been chosen to be replicated in tile for the new terminal at the San Francisco International Airport as part of the San Francisco Art Commission’s public art program. The terminal will open to the public on November 13th of this year.

We are grateful to Justine Topfer from the art commission for choosing Lou’s work, to Don Farnsworth and Tallulah Terryll for making the tile, and to Randy Colosky for his help with the installation.