Shaping a Master Printer

As part of the exhibit “Closely Considered – Diebenkorn in Berkeley” at the Richmond Art Center, Renee Bott was asked to speak this last Sunday on her experience working with Richard Diebenkorn. Here are some of her recollections.

By Renee Bott

When I look back at the years I worked with Richard Diebenkorn in the studio of Crown Point Press, I appreciate how that experience shaped my vision of what it meant to be an artist and, in turn, what it meant to be a printer. Over four years, Dick and I worked together on a total of four projects. We created a total of 20 editions.

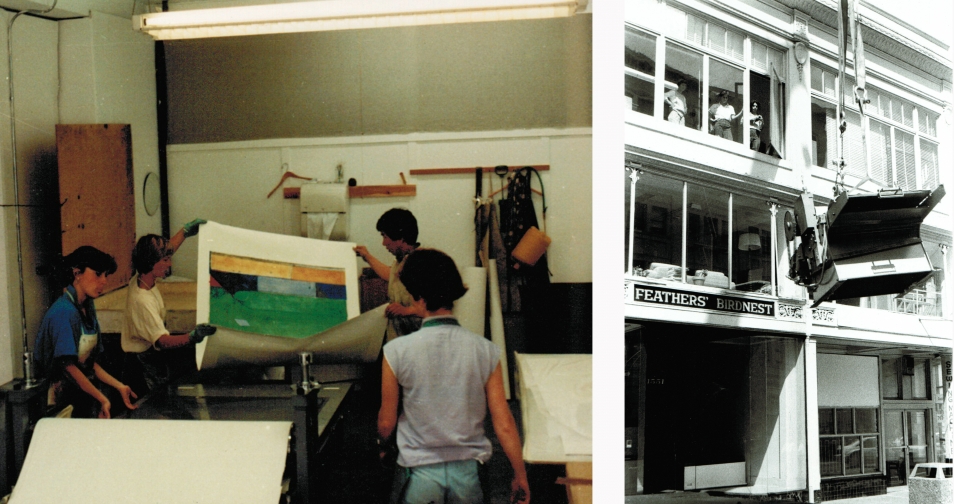

I was 24 years old in 1985, and only a few months prior to meeting Dick, I received my master’s degree from the California College of Arts and Crafts (as it was then known) and was hired as a printer at Crown Point Press. At that time, Crown Point Press was located in downtown Oakland where Broadway intersected with San Pablo Avenue in a beautiful old retail space. Kathan Brown asked me to step in and help the three senior printers make and print the largest, most ambitious color etching that Diebenkorn ever created: Green, 1986.

As I worked in the back room steel-facing and preparing enormous plates, I was worried that I needed to be perfect. But Dick, with his certainty and quiet confidence, warmly welcomed me into his work ethos, a journey that accepted all, imperfections included.

Years later, the Loma Prieta earthquake struck and displaced Crown Point Press from its Folsom Street studio. It was an uncertain time, as Crown Point was forced to find temporary refuge for the gallery and studio. Kathan found a space several blocks south of the old location. It was an old garage that ran west to east for one city block between Folsom and Shipley.

The space was dank and dark, with florescent tubes that cast a hard blue light—a stark contrast to the beauty and grace of the Folsom Street studio. The earthquake had disturbed the homes of thousands, including the city rats. The rats often visited us, scurrying along the pipes that ran over our heads. After a while, our squeals of horror turned to nonchalance as we realized that they, too, were just looking for a new home.

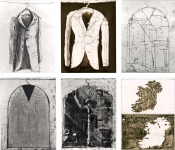

It was in this environment that Kathan asked me to lead a project with Dick to make a set of small etchings for Arion Press’s book of poems by Yeats. Despite the chaos, I remember feeling so grateful to be given this chance to work with Dick again, even if we were in what felt like an underground cave. At one point near the end of that project, Dick, Kathan, and all of the printers gathered for lunch around a small coffee table. A rat ran by on a pipe above our heads, and a silence descended on the group. We all prayed that Dick would not notice our visitor. After an awkward moment, Dick smiled and asked “Was that one of our furry friends?” We all laughed hysterically. Dick was such a humble man. I believe he felt gratitude that we were all there with him, working together, even if it meant having to work around “furry friends.”

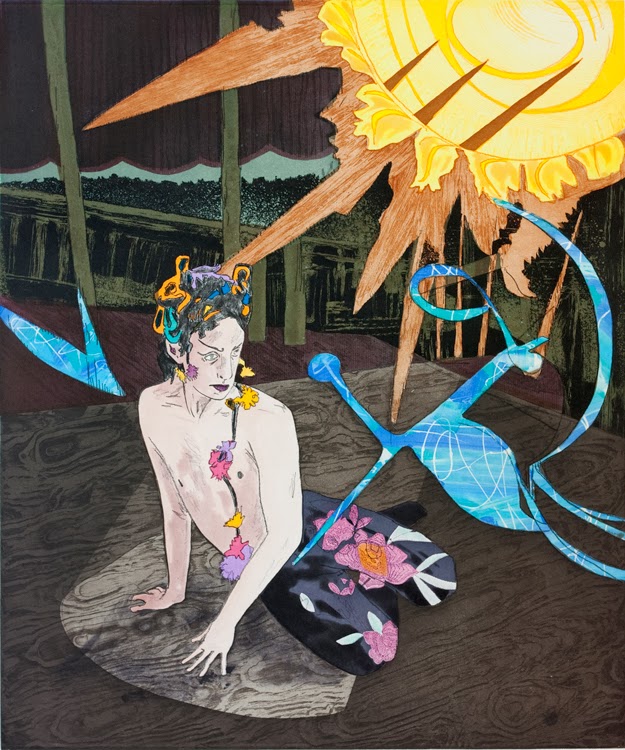

The six small plates created for the Yeats books were presented to Andrew Hoyem of Arion Press at a lunch prepared at the Dienbenkorns’ Healdsburg home. We drank crisp white wine and ate the lovely salmon that Phyllis, Dick’s wife, had prepared. After lunch, Dick asked me to show Andrew the prints. I untied a small portfolio containing the six images. Carefully turning the prints over like pages in a book, I gave everyone a moment to admire the work. No one said a word, but I felt that we were united by the prints.

As I prepared to leave, Dick put his hand on my shoulder and told me he liked the way I had shown the prints to Andrew. It felt like a ray of sunlight on my heart. His grace and humility stay with me to this day, informing my life’s work as a master printer.

.jpg)