Collector Profile: Ross Evangelista

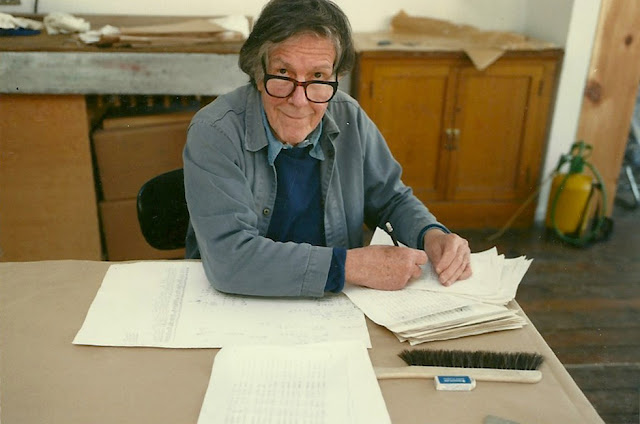

When I was in New York earlier this spring I had the good fortune of being invited to our client Ross Evangelista’s house for lunch. Since finishing graduate school at Fordham, Ross has been working in the financial services industry. Mike, Ross’s partner, enjoys moderate doses of art viewing and gives Ross plenty of latitude when it comes to collecting. I was curious to see Ross’s collection, and I never turn down an offer for a home-cooked lunch. Mike commandeered the kitchen while I spoke with Ross about his relatively new obsession: collecting art.

Renee: Can you repeat what you were saying to me earlier about collecting art?

Ross: There’s a tendency for collectors to be obsessive. There’s something about collecting and obsession that are related to one another. Collectors end up getting more than their walls are capable of taking. Mike is laughing because he doesn’t think that’s healthy.

Mike: We’ve actually had discussions about whether putting paintings on the ceiling was an option. Or could they go behind the doors? That one little bit of wall space there…that I have…that has the Buddhas on it…how about if we just wall-board that? That would actually then give him more space. Limited wall space is a challenge—he can have two or three pictures propped up against the walls. I make him shift them about.

Ross: So whether or not it’s true for every collector, I don’t know, but I’ve spoken to a few collectors, and they say, “Yeah, it’s kind of a disease.” Gallerists are always saying not to sell anyone, especially the young artists.

Renee: Don’t sell them?

Ross: Don’t sell them. Don’t put them at auction. So what is our option? Basically, accumulate. I have spoken to some collectors who say that they do sell some works, and they put others in storage. We don’t have the luxury of storage, and I’d rather live with my pieces. What happens is it all gets to be more fun. Somehow, they find their place somewhere.

Renee: What about the idea of curating your collection? I have a friend who’s an obsessive collector. He decided to build a closet to store his extra work. He curates his own shows! Every month or two, he pulls out a new set of work and rehangs his apartment.

Ross: Wow. Does he do it himself, or does he have people helping him?

Renee: He does a lot of it himself.

Mike: Thank you for that great suggestion. (Sarcastic laughter) I like that idea a lot!

Ross: I’ve considered that also. That’s sort of what we do, especially when we get new pieces. We want to live with them, so when a new piece comes in, we often have to move others around. Really it’s a function of size and space—like the Auerbach prints that I got from you that are in our Long Island house instead of our apartment, because there’s more wall space out there.I’ve considered curating, but you have to rehang and repaint the walls. I sold a print in the bedroom, and I haven’t even filled the holes in yet! Plus, we are in desperate need of better lighting.

Renee: When did your art passion begin? Is this something you’ve been doing for a long time? Or is this something that started recently?

Ross: It started about six, seven years ago. I’ve always been interested in art. I studied architecture, drawing, and studio arts in college, but never had the income to buy art. I moved around a lot before that. I lived in Connecticut, the Philippines, Germany, so acquiring art never occurred to me, since I lived out of two suitcases for a long time, because you’re only allowed two suitcases on international flights.

I think what eventually triggered my interest in collecting was getting exposed to online art blogs such as Modern Art Obsession and Artmostfierce as examples, which are (were, in the case of MAO) run by long-time collectors. Both of them featured “Buys of the Month,” which would feature prints by respectable artists at reasonable prices. Phillips de Pury & Company was also around the corner on 18th Street. We would sometimes go and look there, realizing full well that I couldn’t afford to buy at the time.

Back then, Jennifer Beckman had started something called 20X200. I started out buying from 20×200. I must have 20 or so prints from Jen. Afterwards, I started purchasing limited edition prints from Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Photography. I also have a few limited-edition Aperture and AIDS Community Research Initiative of America photos (ACRIA) too. We try to go to galleries every week. When we travel, seeing art is definitely part of our agenda, which Mike doesn’t always like. You like seeing art, right?

Mike: In moderation.

Ross: In moderation, yeah. For me, the key to getting into collecting was understanding that art is accessible. I let go of my fear of asking gallerists questions. I was trying to understand what artists do. I think a lot of people are afraid of art collecting because they’re afraid of asking questions. They’re afraid of not “getting it.” Of not knowing. My real collecting started after I got over that hump.

Renee: Do you remember the first piece you bought from a gallery?

Ross: Sure. This is actually the first piece. (Sarah Pickering: Fuel Air Explosion). It’s part of her Explosion series. That’s my first real print from a gallery, from Daniel Cooney Fine Art. He’s a great gallerist, by the way. This is also Sarah Pickering. (Sarah Pickering: Abduction)

Renee: I love that one.

Ross: It’s awesome right? I had that framed at Bark Frameworks since it’s so special to me. New York Magazine featured them as the “best” framer in NYC. I didn’t know then how dear “best” framing is!

Renee: Tell me a little bit more about her.

Ross: As I understood it, her body of work then had a lot to do with keeping public order. She is from the UK, and a number of her series depict training grounds for policemen, firefighters, and investigators. In her photographs, you see what looks like a real street and real houses, but they’re fake. They are training sets. She worked with public officials to accomplish this. She’s a bit of a pyro, right?

Renee: Yes.

Ross: This is called Abduction. For this piece, she worked with the fire department. They would create a whole room and set it on fire to train firefighters how to look for a fire, how to fight them. They would leave clues. If you look closely, there’s a gun on the couch. It’s a very active piece. Even the explosion is a bit narrative. You ask, “How did this happen? Why is there an explosion? Is this a war zone?” You don’t know because they are so well composed.

Renee: It’s stunning!

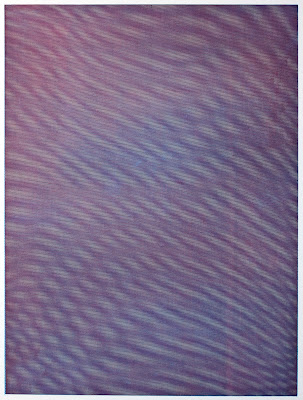

Ross: From there, the floodgates opened. I finished grad school around 2005. I didn’t have much money. I still save up and try to look for good value and for what is interesting to me. Tauba Auerbach’s 50/50 prints were probably my next large purchase. I can’t remember if I bought all three at the same time, but I have three.

Renee: I think you did. You have the Zoom In Zoom Out. It’s fabulous! Mike said that you’re reading all the time, educating yourself. Do you find that you want to get informed after walking into a show and being intrigued by what you see? Or are you doing research first and then seeking out the artists that you read about?

Ross: I think both. I am definitely very research-driven in terms of what I look at. Even though I can’t add something to the collection, I still read about it. I’d even include it on my blog, which is a repository of works I own and works that I’d love to own. I have a lot of art books. I’m not sure about the real purpose, I just like doing research. Otherwise you are just a buyer. I don’t want to be just a shopper or a decorator. I want to be informed about what I’m collecting.